Searching for Peter

When I was a boy growing up in Montana, Peter Hazelbaker was but oral family history. In September of 2008, a series of remarkable circumstances led me to Pennsylvania, and Peter’s final resting place.

I do not represent myself as a genealogist. I am grateful for the online resource provided by Peter Hasselbacher the Younger, and the work of other true genealogists like Jack White, Imogene S. Davis, and Jill Hazelbaker Foley. I will have to admit to being somewhat of a researcher, and having been trained in the sciences, I try to hold myself to a fairly high standard of evidence and reasoning.

I have always been interested in the family history, and truly curious about the nature of the man who came to America to fight colonial English, and wound up being an American settler. A year or two ago, I started looking into these musings more seriously, utilizing my interest in military history, the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and some reenacting which could also be called “practical anthropology” – who else in my family would get obsessed about quill pens, period inks, and flint and steel fire starting. Having studied a bit of anthropology as well, I was very curious about the power and accuracy of oral history, this time as it pertains to my family.

I gathered information from the internet, including texts of early settlement of Washington County. I read that Peter was buried in the Sphar family graveyard. “Why there,” I wondered. I found where the old Allen Township was. I looked at online maps, and even satellite photos. I found Dunlevy, PA. Dunlevy was the maiden name of one of Peter’s daughters-in-law, my GGG-Grandmother. I zoomed in, and saw Sphar road. Chills. Online, including Peter the Younger’s web site, I found a sketchy description of where the graveyard was located.

In August of 2008, my son decided to move to Pennsylvania to establish his own place in the world. A month later, it was time to take the rest of his belongings and his fine German Shorthair Pointer to him. This was my opportunity that I’ve wanted for decades, to go see the land that Peter and his sons saw, and with luck, find where he is buried. So I packed up my friend Diane, the boxes, the dog, and headed east.

After the visit, we headed towards Pittsburgh and that large oxbow of the Monongahela River that once held Allen Township. True to Murphy’s Law, I had forgotten my file folder of maps, satellite photos, the sketchy directions to the grave yard, all.

What I could remember was the paraphrase “turn right at the bakery, do not take the road to the right (?!?), and it is behind the barn.” Based on what I remembered of my research, I exited the interstate and headed south in highway 88. Before I knew it, there was a Hostess outlet bakery on the right, and pulling to a sudden stop, I found myself staring at a small street sign that said SPHAR. After spending some long seconds in stunned amazement, I headed up the hill on that gravel road. That September week still saw warm days and green trees covering the road.

I kept silent about the significant drop-off on my left, and the way my low-slung van’s wheels were slipping on the gravel. At length we came to some outbuildings on the left; they didn’t look promising, but I got out and hiked up the hill to see what I could see. Most significantly what I saw was a farmer staring at me from his farmhouse.

Looking SW towards the modern farm house,

and the old barn just right of center.

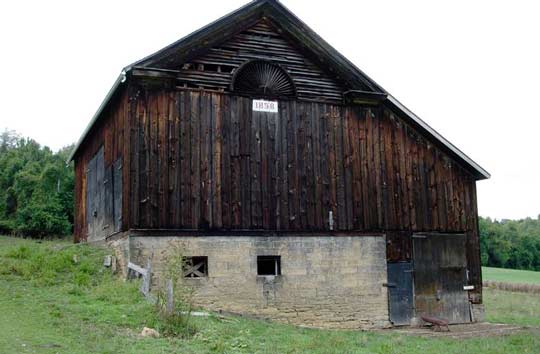

He wound up walking down the road to meet us, and I introduced myself, and what I was looking for. “Hazelbaker!” he exclaimed, “Some of your kin was looking for their grandpa or something last summer!” “Did they find him? Is this the old Sphar farm?” “Yep, this is the old Sphar place, but no, just the old graveyard, almost everything is down, and unreadable, they said they found D… something, but no Peter, wasn’t that your Grandpa’s name?” Yep, sure was. But, he was willing to let us have our own look. Going uphill further, south bound on that small Sphar Street, we came to the old barn mentioned in the account, on the right side of the road heading south. He told us the old Sphar farm house was behind where the barn stands, and all of that is gone. He said the graveyard was behind the barn and to the left, about 45 degrees bearing from the barn.

Sphar barn, dated 1858. Note the apparent age

of the original foundation below the cinder block.

The search didn’t take long to find the old graveyard. Indeed, nearly all the stones were down, and most of them made from field stone. The only stones I saw with professional carving on them were three, dated within approximately 2 decades, 1830-1850.

Diane called to me, “Is this a D, or a P?” I looked up to see a roughly obelisk-shaped stone, approximately 24 inches high. Walking around to the front of it, carving could be plainly seen.

I don’t remember if I went to my knees or not, but I do remember that feeling. “My God,” I whispered. “I’ve found him!”

It is one thing to have a personal desire for this to be Peter’s grave, but what is the logical evidence? First, I feel that previous people have looked at this stone with 20th century eyes, when it was carved with an 18th century hand, when such markings were very individualistic. There are clearly marked serifs atop the first letter, and at the top and bottom of the H. The top serifs of the H are in line with the top serif of the first letter. In no hand script or printed letter that I’ve been able to find from the period does any upper case D have an extension of the vertical above it. That extension is clearly intentional and terminated by the serif. Lower case D is out of the question. That is clearly P.H.

I consulted a new friend, a professional government archivist in Germany. He holds that it is a P. I consulted a director of a German-American museum in Pennsylvania, and he holds that it is clearly a P. I put it to a group of amateur historians and re-enactors on the East coast, who inspect original period documents, and search graveyards of the 1700s. All feel it is P.H. (Click here for additional discussion about calligraphy of the period.)

Why would that have to be a Hazelbaker/Hasselbacher in that graveyard? So far in all my research of the Sphar, Shively, and Furnier families, I can find no other relative or in-law to any of them with a surname beginning with the letter H, except Hazelbaker. The only other one was Peter’s son Peter, who died mere weeks after his father and was buried beside him.

Peter went to Pennsylvania some short time before he died in 1800. He died unexpectedly, in what was probably a newly cleared land, leaving a young widow and seven children. Elizabeth Shively Hazelbaker no doubt turned to family at this time of need to bury her husband. Peter was buried in Sphar graveyard, near the house, because he was a relative. Elizabeth’s sister, Anna Maria, married Mattern Sphar in Williamsburg, VA, in 1772. Peter was buried with family. That also shows the family connection for the move from Virginia to Pennsylvania. Every identifiable grave in that graveyard, including Furnier, is either a blood relative or relative by marriage of the Hazelbaker family.

Cousin Mark Hazelbaker of Madison, WI, wrote to me that he feels, with this evidence, we may fairly assert that Peter’s final resting place on Earth has been found.

These folk were early pioneers on newly cleared land, and used what materials they had at hand to mark the graves of their loved ones. It is reasonable to assume that there was not a great amount of money to be had for a professionally carved stone, even if one was to be had. It was not uncommon for a pioneer family to bury a loved one by a land mark familiar to them, say, a boulder, or to put a small but special marker on it, if any at all.

Looking at that stone, if you could forgive a flight of fancy, I can fairly imagine a son, perhaps John, 17 or 18 at the time, or Peter, 16, or Daniel, 14, carefully carving that stone by hand with a broken heart.

Craig W. Hazelbaker

Cedar Rapids, IA

1/25/09

“‘Tis sweet and commendable in your nature, Hamlet,

To give these mourning duties to your father:

But, you must know, your father lost a father;

That father lost, lost his.”

…William Shakespeare